“To risk one’s life is first, perhaps, not dying. [...] I interrogate risk in a manner that does not permit its evaluation or its elimination, within the horizon of: not dying. How are we supposed to imagine that the certainty of our end might not, retroactively, have any effect on our existence? From the furthest edge of this certainty, we know that one day everything we loved, hoped for, and accomplished, will be effaced. And what if not dying in the midst of our lives was the foremost risk of all, refracted in the human proximity of birth and death?”

— Anne Dufourmantelle, “To Risk One’s Life,” In Praise of Risk

[Man in Chainmail Tunic Posing as a Dying Soldier] (ca. 1863), Adrien Constant de Rebecque

I did not die when I could have. From 12 to 14, between the onrush of cars, the elevation of housing blocks, the intimidation of knives, I meditated on dying. My life expanded under the density of that desire for relief and mercy; I was a carrier bag stretching out in capacity, risking the beginnings of a tear that would become an irreparable hole. At 14, at the end of my patience, I posed an ultimatum to myself: “Do you want to live, or die? Make up your damn mind.”

I realize, in retrospect, that I suffered so deeply against my mother’s abuse and bitter prophecies because I believed something else—someone else—was possible. The facts of who I was and what I wanted my life to be—what my life would irrepressibly become—glowed irresistibly at the core of me. They remained true in spite of my ruined self-esteem, even in the presence of the utter contempt and distrust I felt towards myself and other people. She was lying, and a large part of me believed her, and that really fucking pissed me off. Having no power to remove myself from her diseased forcefield pissed me off at least a hundred times more.

At 15, I met the person who would become my best friend. I began to move without compromise towards the things that called me: literature, theatre, books, writing. I don’t think that a wonderful life lay on the other side of my decision to live, as though my decision was a door I walked through into a new room. Rather, my decision was an irresistible manifesto which insisted I make different decisions from what I had before; that I imagine myself to be someone else entirely. By making it, I committed myself to living by its creed, which, like a spell, has made courage and goodness inevitable. Having put myself up to the terrifying task of not dying, I live with a religious kind of devotion in the unfolding of my life.

Two Nude Male Figures Struggling Together (1709–10), Nicolas de Largillierre

What about the many of us who live seemingly against our will? Faced with the overwhelming scale and myriad forms of violence in the world, it makes sense to feel the death drive grow keen, lurid. So many people want to die. So many people declare us doomed.

Doom is the easier tool. Doom allows us to come to a conclusion more quickly, and stop having to move. If we decide it’s over, we get to give up and lean away from the risk of having to do something, of taking that journey, of unfolding into the people we know we can be. Doom is the hope of escaping. It is a cop-out which leaves the narrative thin, linear, easy to wrap our minds around. If you risk letting it thicken, you’d have to learn to navigate a more complex story: nonlinear, spiraling both down and up, inconclusive, continually changing as we make different choices. Rooted not in fear, but in daring and in the values we hold to be true, necessary. You’d have to learn to hold complex emotions that swirl into one another simultaneously, and to make sense of the world that way.

Despite the appearance of giving up, I find that the desire to die is in fact a relocation of hope. Unable to hope for alleviation, relief, and healing through life, one hopes to find it in death. A total reset via annihilation. Clean, final. The end of everything (supposedly) ensures the end of suffering. In a way, dying is more comforting and reliable than not dying, because death offers the certainty of its outcome. Life never quite does.

That’s why we run, right? We run from what feels unbearable, impossible, in excess of our abilities to manage. Running protects you when your systems aren’t ready to take the sheer force of experience. Though I had chosen not to die, my body continued fleeing. Not knowing the limits of my body and its intertwined systems, I operated on the limitless desires of my ambitions instead. I pushed my body-mind way past its zone of safety, and it shut down. I spent about 3 years of my life heavily dissociated, operating as an avatar which shielded me against immediate life. I floated around in the escape pod my body-mind had pushed me into, waiting to be rescued.

Not dying does not offer escape from experience. It invites you to plunge in, to be unmoored, taken over. Not dying demands the courage to lose control, to fall suddenly into action, to learn while doing, to go missing, to be held in suspense, to climax at the hands of an other (who might yourself), to be invoked by the specifics of your context, to become whatever life asks you to be. To enter the arena of life even when hope leaves it. To be so intimate with life that you no longer need a self to exist. Not dying asks you to find life in everything, even confusion, loss, and suffering.

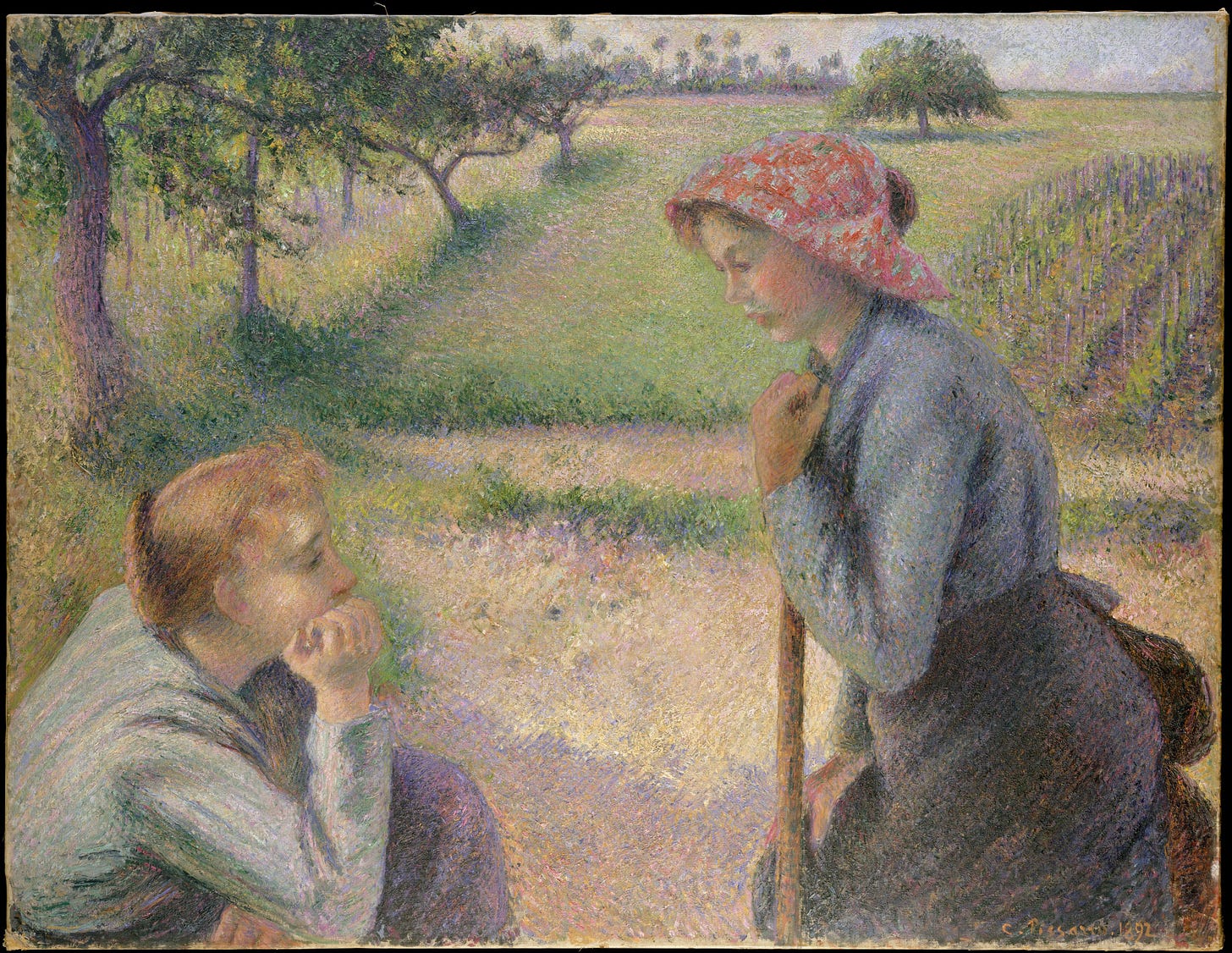

Two Young Peasant Women (1891–92), Camille Pissarro

Is there nothing to hope for? Devoid of hope, I find there much to cherish. Look at the blue sky and those clouds. That perfect tree. That book, film, or album that changed your life. Our earnestness and resilience which permeate past borders and polarities. Your friends unfolding, ageing and changing and deepening as the people who came before us did. Be real about the magnificence that is with us in the horror. It does not teach us to hope. It teaches us to pause, love, and act.

Against the prophecies of doom for 2025, astrologer Alice Sparkly Kat wrote: “The future isn’t something that happens to us. It’s what we build together. That is what we use astrology to narrate—a determined vision of the future that supports our inventiveness.” Tell me your version of the story, the one that sounds wishful, innocent, foolish; the one that sounds drastic, angry, fevered with poison. Let’s use our tools (of spirit, body, mind, and heart) to divine a vision so clear and immersive that we begin to walk right into it. Let’s use hope as a tool not to move towards escape, but to walk right into the fire, willing to be changed, believing we will come out not on the other side, but right at the heart of where we began.

Not all of us have the means to recognize, much less move through, our suffering. Numerous systemic, historical, intergenerational factors exacerbate our struggle, and alienate us further from each other and ourselves. Giving one another rope to pull ourselves up with takes collective effort. It takes the building and maintenance of ecosystems of resources, direct aid, and awareness.

We will not give up on one another. We will risk arriving at the clarity of our desires and intentions; risk the unnameable and its gift of loneliness; risk heartbreak. Stopping midway, the complexity of information seems contradictory, overwhelming, and increasing without end. Persisting on the path, contradiction gives way to luminous truths, from which clear actions may arise. We cannot afford to have a little wisdom; we must have a lot of it.

@hidden.ny

Perhaps, more than anything else, we must risk trusting one another. We must move against the mechanisms of isolation and polarization that continue to push us apart. People who wish to singularly hold power over others have a dreadful inkling of just how magical and powerful we are together. They fear other people, and they teach us to feel the same about one another. Nonetheless, life reminds us of our inherent interconnectedness. We exist because so many other people, species, and things exist. I am because you are. Although I may fear the vulnerability and precariousness of growing close to you, and I may fear the ensuing promise of loss which issues out of intimate attachment—I muster the courage to go towards you. I promise to study and discover how we can co-exist.

“I also don’t believe this sort of, like, ‘Everyone should be very self-sufficient, and you don’t need anyone else to love you, you just need yourself to love you.’ I think that’s nonsense. I mean, of course we’re all connected in a network of human relationships all the time which sustain us. I mean, people are out in fields picking crops so we can eat. People are making clothing that we have to wear. So the idea that you can move through the world as a self-sustaining individual is a fiction. It’s a delusion, really. [...] Human relationships are very important. They’re very sustaining, in whatever form they take. They don’t need to be conventional; they can be very unconventional. But they’re not just optional. You can’t just opt out of the rest of humankind.”

Sally Rooney on ‘Conversations with Friends’, Louisiana Channel

Mark Fisher wrote that “[o]bserving humans under capitalism and concluding it’s only in our nature to be greedy is like observing humans under water and concluding it’s only in our nature to drown.” Who else—how else—could you be, could we be? Who could we be under different conditions, making the choices that are true and right for each of us? What would you do if what you wanted was possible? And even now—right in this moment—what could you choose differently? Could you speak or act in a way that feels more risky, a way which votes into the reality you want?

This is a necessary exercise of imagination and action. In asking these questions, we begin to reopen foreclosed possibilities. We begin to stretch spacetime for one another.

Ancient holy wars

Dead religions, holocausts

New regimes, old ideas

That's now myth, that's now real

Original sin, genetic fate

Revolutions, spinning plates

It's important to stay informed

The commentary to comment onOh, and no one every really knows you and life is brief

So I've heard, but what's that gotta do with this black hole in me?— Father John Misty, “Holy Shit,” I Love You Honeybear

Before we move at the scale of movements and revolutionary change, we must learn to move at the scale of you and me. What you and me need is to pass time together. We need to talk. We need to listen, and share, and learn, and devise a relationship around the mystery of each other. Finding ways to do that in this very moment, as so many constrictions imagined, implanted, and enforced seem to close their jaws around us—this is our most critical task. It is more important than being right, or winning, or scrambling to have all the facts.

The proliferation of academic and journalistic terminologies has, on one hand, empowered more of us to understand and articulate our cross-cutting realities. As these terminologies hit half-life, as they degrade by dilution and misuse into impotency, how can we continue the conversation? More importantly, how do we invite more people in, especially those for whom such language has felt and been alienating and exclusive? Feeling the pressure “to stay informed/ The commentary to comment on,” we may have built a fortress of big words and people who use them around us. Something that makes you feel articulate and correct may mean nothing to the person on the other side. How can we take sufficient care of the ego that we no longer need to service it in these ways? How can we be freed up to act and speak in deep service of others?

In “Holy Shit” by Father John Misty, this disconnect manifests between the scale of collective meaning and the scale of individual pain. He captures this gap by indulging verses in words which hold meaning primarily on one side of that gap: the systemized collective. Spanning religion, culture, and politics, the list of keywords feels increasingly meaningless as he goes on: “Age-old gender roles/ Infotainment, capital/ Golden bows and mercury/ Bohemian nightmare, dust-bowl chic”. Trying to “capture” the cultural “milieu”, our language loses sight of each other. We become cultural phenomena, data points being scanned for pithy patterns. In those spaces, the scale of language exceeds the scale of connection.

Father John Misty strains this disconnect by transposing immense, collective phenomena (or hyperobjects) onto personal experience. Vast, uncontained phenomena become immediate horrors through acts of metaphor: “this atom bomb in me” and “this black hole in me”. While the huge sweeping terrors out there certainly concern us, what feels most intimate and most urgent are the terrors and mysteries within us.

Crucially, through his transposition, Father John Misty suggests that inner and outer phenomena are the same. They are as vast and horrific and confounding as each other. They are, actually, no different in scale, in their vastness and immediacy. Those large scale phenomena are not far away at all. They are right here inside of us, ticking softly, consuming gas and debris from nearby stars. What would it mean to think of climate change as something occurring in us? How is war a part of our daily diet?

Venus and Mars Embracing as Vulcan Works at His Forge (1543), Enea Vico

“Holy Shit” culminates in an invitation to move away from religious, political, and cultural terminologies, and to return to our bare, basic ideals, to the you and me that precedes more statistical evaluations of love:

Oh, and love is just an institution based on human frailty

What's your paradise gotta do with Adam and Eve?

Maybe love is just an economy based on resource scarcity

But what I fail to see is what that's gotta do with you and me

How would you describe your paradise or aspiration for the world without the language of religion? How would you engage with me, directly, plainly, without the calculations and veneers of culture and economy? Rather than rely on the words manifested for sweeping, macro phenomena to name our experiences, we can invent language for the small, specific, and granular at the interstices and synaptic gaps between us. We can find ways to live the fictions of our hearts without compromise, before a single word is spoken.

What are you and I about before words rush in to tell us who you and I are, or how we be together? How can we stay suspended in that gap without rushing for language? How can we resist immediate or total resolution in the stories we tell together and about each other? How can direct experience precede the mediation of language? How can I learn to be with you?

"It is dangerous to undermine the belief that the subject might regain her "self" and construct herself through an immediate decision. This belief forms the armature of our myths, the very root of the political. But it is mere fiction that the subject will find herself in action, a greater fiction than anything else. But it is attractive. We have such a strong desire to recognize ourselves in our acts, our judgments, our assertions. Whereas, in fact, metaphors, nebulous images, and uncertainties describe us best. Being in suspense returns us to the penumbra, to a point of relative blindness, and to a certain manner of holding fast to this point. Holding fast, something else appears, another limit, another shore."

— Anne Dufourmantelle, “In Suspense,” In Praise of Risk

⊹₊。ꕤ˚₊⊹

Absolutely loved reading this. Thank you. 🤍